Unexpectedly, or perhaps, expectedly, I have more to discuss on the topic of the Mangalore Tile. Much more in fact—a disclaimer for what is to come. In my previous blog post: From Marseille to Beyond Mysore Travels the Mangalore, I wrote about the history, cultural value and manufacturing source of this conspicuous roofing material native to South India. Now, I shall speak from experience of actualising a roof constructed with it. Thus, the following will read as part story and part case study, giving first-hand insight to what can go wrong and what can go right in the making of a pitched roof.

“When did the pitched roof stop being a necessity? The dirty secret of modern architecture is that it never did. We stopped using it without any superior solution presenting itself. The omission of the pitched roof is an intentional technological regression, a deliberate forgoing of the best solution in favour of an aesthetic ideal, eschewing function for form—the symbol of a desire for progress instead of progress itself. We choose to endure the inconvenience…”

~ Reiner de Graaf, Four Walls and a Roof, 57

The following occurred well over a year before my visit to the Commonwealth Tile Factory in January of this year, explored in the aforementioned blog post. Yet I have chosen to publish this text after the narration of this visit as the following matter is best digested after having revealed the nature of the material that is the Mangalore Tile.

To See About a Roof

I ride pillion passenger on the back of a Hero Honda Splendour—the driver only a stranger to me minutes earlier. He is Dhandapani; a welder; a roof-maker. I do not know yet where we are heading, only that the person who compelled me to hop on this motorcycle I trust completely. Leaving Auroville the destination we speed towards has something to do with a roof. During the preceding conversation, my Tamil interlocutors decided that rather than be told, I must be shown, hence this journey into the unknown. With a little patience and confidence all would be explained to me in due time.

We reach the East Coast Road then turn right and accelerate towards the western outskirts of Pondicherry. After much traffic and smokey asphalt we enter a quiet neighbourhood dissected by a narrow concrete canal, which we follow alongside for a minute or two. Dhandapani eventually slows his motorcycle down to a halt, notifying me that we have reached. I look to the left and see walls of brick—of stretcher bond pattern, cornered by concrete columns—still in the process of being constructed and soon in need of a roof. Ergo my presence.

The yet-to-be building is a small L-shaped bungalow, its plinth occupying just under a quarter of the squarish plot it belongs to. The green canopy of a nearby raintree—standing alone gracefully in the opposite quarter—is of far greater dimension; a tree that makes the site. The place is further made alive by the movement of half-a-dozen labourers completing the brickwork, which is being executed with a reasonable level of care as the brick is to be exposed.

Soon, I meet the client, the contractor and site supervisor (and much later the client’s elder brother and young nephew, among others) to give consultation. Arguably, alongside Dhandapani the roof-maker, this was a few too many people to be involved with together in such a small project. But what to do? There are many people in this country (the understatement of the century). The client—a general surgeon—tells me his needs and I give input on what needs doing. From this first meeting I developed the internal private habit of referring to him as The Good Doctor, and so henceforth in this writing I will continue to do so. We had actually driven past the hospital he worked in, a gargantuan white mega-building with classical greco-roman flourishes on its facade. I liked that what The Good Doctor was making for himself looked nothing of the same.

The roof plays a primal role in our lives. The most primitive buildings are nothing but a roof. If the roof is hidden, if its presence cannot be felt around the building, or if it cannot be used, then people will lack a fundamental sense of shelter.

Christopher Alexander, Sheltering Roof; Pattern 117; A Pattern Language, 570

In fact, The Good Doctor was adamant about having a Mangalore Tile roof. This being something that has become less and less common over the years within Pondicherry. What he wanted was a pitched roof for a pitch-perfect archetypical abode, in keeping with the local architectural vernacular of South India. This was the element that the contractor and roof-maker were unable to carry forth without consultation. Furthermore, it became clear from observation that the bungalow had been built so far without any relationship in mind with a pitched roof. It had been built in the conventional way as if it was going to be roofed by a typical flat concrete terrace, the now-norm roofing method in many parts of India.

When our meeting finished and only Dhandapani and I remained, we tarried a little longer as I took the opportunity to engage with his expertise. These are the moments where pen and paper come in handy, although drawing with a stick against the earth does wonders too, you just cannot take away with you the results. For most of my questions I usually had answers in mind as this was not my first roof-making rodeo, but I always seek to have them confirmed or improved upon by alternate options. There are plenty of times I simply do not know or I am surprised and who better to discuss a roof with than the person who is going to make it. In this instance such questions include: ‘what mild steel section sizes would you use for the rafter, the valley or hip rafter, and the battens that hold the roof tiles?’; ‘How would you fix the rafters to the top of the brick walls?’; ‘is this size available?’; ‘how long will this take you?’; ‘is this cheap or expensive?’; ‘kashtam?’ (the Tamil word for difficult, that said in a particular tone evokes the question ‘is this difficult?’).

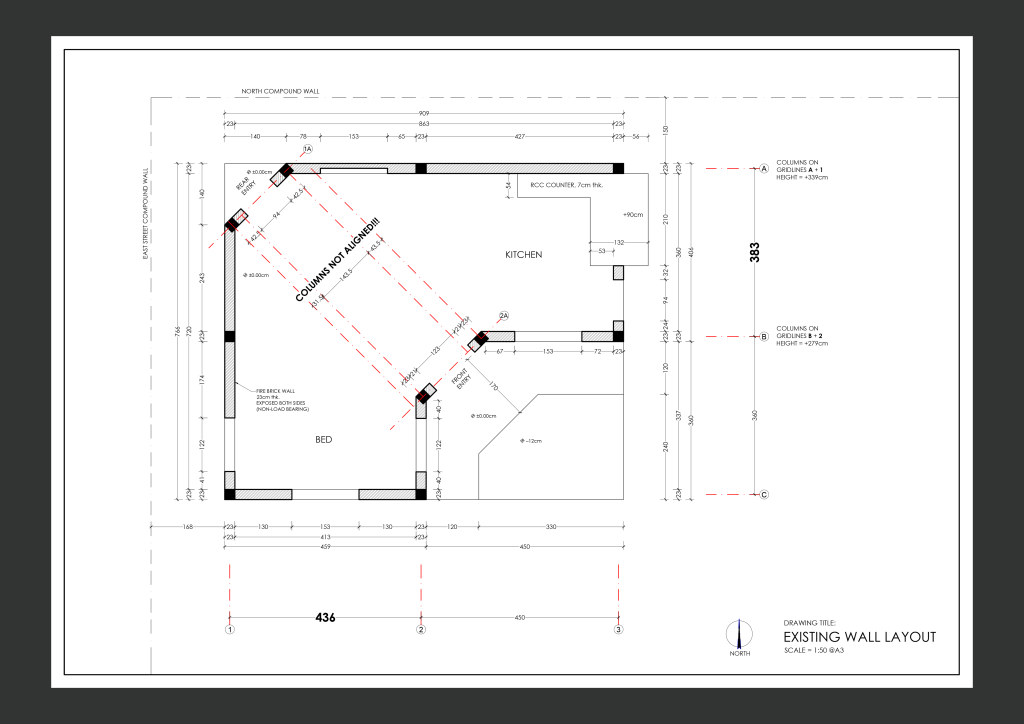

I had asked the site supervisor for a drawing of the building and what he gave me the next day was extremely lacking in detail, let alone basic dimensions. A chicken scratch would have better sufficed. I strongly speculate that the builders never had a drawing to begin with, that what the site supervisor gave me he had only made after I requested it. This meant this was a building drawn once and only in the dirt—which is not a tremendous problem in itself—but I needed accurate measurements. So the following day I returned to Pondy (short for Pondicherry) with my friend Pondy (his nickname at CEPT university as he is natal to this city), and together we took proper measurements. This is when varying discrepancies and issues regarding the building came to light, which would make designing the roof far more difficult than it initially appeared.

These multiple issues were convoluted in contrast to the bungalow’s quaint appearance. I will do my best to describe them succinctly and with much needed imagery included.

- Firstly, the L-shaped building appeared to be symmetrical from the outside, but while making the measured drawings, I noticed that the width of each of the two wings that combined to form the L, differed by about half a metre. Another way of putting this is that of the two lines that form the L, one line was thicker than the other. This meant the building was asymmetrical and therefore it would be tricky in planning—conventionally and ideally—to mirror and continue the roof shape where it would turn.

- What the above also entailed was that the corner-to-corner axis of the L was unaligned, making it difficult to figure where exactly to place the roof valley and its supporting rafter; the most integral structural roof member.

- On top of this, the outer-face walls of the L-shape building were built two feet taller than the inner-face walls. This discrepancy was part of a nonsensical attempt to better achieve a roof pitch, but instead only added another limitation.

What a rigmarole, or as said in Tamil, romba kashtam… very difficult.

Fortunately by this point in time I had enough experience designing a variety of roofs i.e. domes, vaults, filler slabs, concrete slabs and a good number of pitched terracotta roofs. Hence, I managed a solution as will be shown and discussed at the end.

Barring the as-built discrepancies of the structure, one other aspect to contend with was persuading The Good Doctor to have the roof insulated. Initially he wanted terracotta ceiling tiles so he could experience a warm textured ceiling within the bungalow’s interior, which in construction involves placing a layer of ceiling tiles which the roof tiles then clip onto. This method I consider practical for outdoor areas such as verandahs, or indoor spaces if the ceiling is high up—minimum 14 feet—so that the heat the tiles absorb has less radiating effect towards people. Also, keeping in mind that the brick walls were exposed internally, having a terracotta ceiling would make for too much clay colour without any contrast, plus it would severely darken the interior, even more-so as the flooring was planned to be laid with black Kaddapa stone. By stating to The Good Doctor that he would be cooked inside the bungalow during the summer months without an insulated roof—coupled with the other concerns—I was able to convince him to invest in the best possible outcome.

To Not Make a Roof

Before I reach the resolution of The Good Doctor’s roof, I am going to make a time jump six months forward to briefly discuss a different Mangalore Tile roof, demonstrating what can go wrong.

This time, I am driving myself to Pondy. Not via the ECR but instead the Old Auroville Road. Like countless times beforehand, I head there to have biryani for lunch. At two-thirds of the journey, I receive a phone call and have my companion riding pillion passenger check who it is. It was Montie (not his real name), a former colleague. Now more curious than hungry, I pull over in the shade and answer. He quickly explains to me that he has a debacle with a Mangalore Tile roof that he had recently designed and constructed. I said I would get back to him after lunch and reviewing his drawings and photos.

After perusing Montie’s work I was quite disappointed and a little shocked considering our shared level of experience, which I soon communicated to him, starting with some dastard commentary before giving constructive feedback.

The project was a large gable roof for an outdoor seating area of a restaurant. It was clear as day from the photos that the roof was at risk of catastrophic failure. The roof was sagging; its battens were sagging; its beams were sagging. All this sagging was caused by the inadequate spacing of the structural members.

Conventionally roof rafters—traditionally made of wood but now more often of steel—are spaced between 45–80cm apart for a Mangalore Tile roof. One can even stretch this convention up to 120cm, but this requires the rafters to be larger in profile and therefore more expensive. Montie had provided a spacing of 210cm. Consequently the roof sagged, a portentous warning of potential collapse. He clearly forgot witnessing me drafting and redrafting similar roofs innumerable times and discussing them with him, as well as the plethora of built examples in Auroville, and, ultimately the fact that each single Mangalore Tile weighs about 2.5 kilos; and a roof of this size would contain at least a thousand tiles, equating to 2.5 tonnes, the equivalent of having the weight of a Toyota Land Cruiser or four-wheel drive Mahindra above your head.

Decisively, with some added cross-bracing between the columns and beams plus a couple of extra rafters, the sagging was rectified. From here on all was well.

To Make a Roof

Returning to The Good Doctor’s roof, after some mental gymnastics a solution was produced that Dhandapani executed as accurately as I could have hoped. The drawings and notes describing it I will attach at the very end in the format of an appendix.

Before concluding the narrative, there was one noteworthy situation on site that had to do with the valley rafter, the structural member located at the junction of the roof where the building turns to form an L. As the valley rafter had to sit above the front door opening, it required additional support that was initially lacking, as the existing lintel was made only to support the door, not also the most pivotal and weighted part of the roof. A second ‘lintel’ or beam was added, made of steel, so that the valley rafter could be fixed to. A problem arose however as Dhandapani did a minimal—near negligible—amount of welding to fix this integral junction. It was like using a single staple to combine an inch thick printed manuscript. I immediately thought about cyclones and was unconvinced, I needed more than his thumbs up approval, and so with the backing of The Good Doctor’s nephew, Dhanapani then added extra steel and welding to reinforce the junction to the point it became superfluous. Better safe than sorry.

In conclusion, this roof was a fun little project but was not without dilemma. It took about 6–8 months to complete, when realistically it could have been constructed easily within a single month or ideally two weeks (the logistics were outside my scope). In the same span of time I observed a building twice as large that I had worked on be constructed from foundation to roof. I deduced this prolongment owed to several interpersonal conflicts that I was not privy to, but I know at one stage the contractor was kicked off the project for dispensing the client’s budget on beers rather than Mangalore Tiles, which had the negative effect of forcing Dhandapani off the project too after he had completed 95% of it, having only the tiles left to lay. This meant that I had to correspond with another person, who unlike Dhandapani, was young and inexperienced, having never made a similar roof before. Luckily for him it was just a matter of laying tiles and having me explain to him in detail how to make a gutter for the roof valley. All of this was enough drama to be portrayed in a Sun TV soap opera.*

If there is any one lesson to take away from all this, it is that always plan and build the walls in relation to the roof, and vice versa. Otherwise, romba kashtam…

*Sun TV is an Indian Tamil-language television channel.

Appendix

Summary of Design Considerations

- Measured drawings

- Roof shape design simplified

- Roof slope 28 degrees

- Insulated ceiling

- Optimisation & reduction of steel members & therefore costs

- Least demolition required

- Ridge beam to connect rafters

- Other design considerations

Design Considerations

- Completed a measured drawing of the building under construction, as the diagrammatic drawing given was inadequate to make any accurate working drawings of the roof. Upon reviewing the measured drawings, all as-built measurements make it tremendously difficult to propose a simple or easy solution i.e., the walls being of various heights, the rooms being of various widths, the columns not being aligned. Essentially, the walls and columns were built with no consideration of the roof.

- Roof shape designed for superior strength. More turns, means more joinery, means more weak points. The proposed roof design has a single turn, which minimises the areas requiring precise waterproofing to a single area. The roof design reconciles the inconsistencies in the building, especially the misalignment of the columns. Emphasis of the roof design was given to how it appears upon entering, and from the interior.

- Roof sloped at 28 degrees for ideal rain protection. The marginal increase in wall height required (for the south & east most walls) meant that this slope could easily be achieved at insignificant cost. Concerning proportions, the proposed slope makes for an ideally shaped roof, both aesthetically and practically.

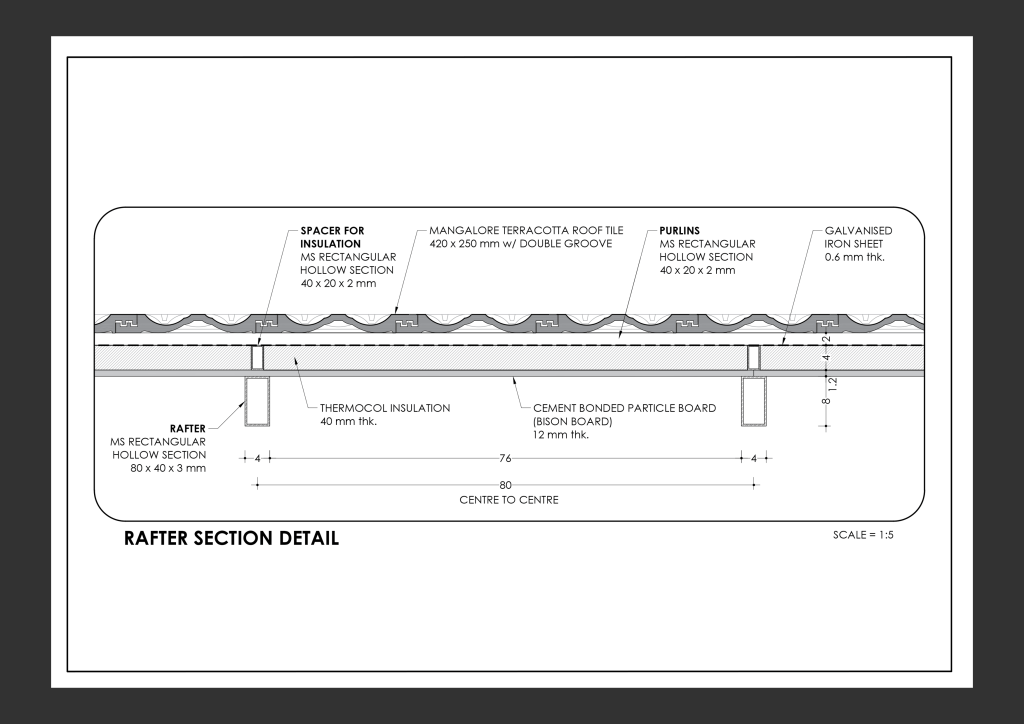

- Proposed an insulated ceiling (as opposed to the initially suggested terracotta ceiling), incorporating bison board, thermocol insulation, and G.I. sheeting for optimal thermal performance responding to the local climate. This was strongly advised as the alternative would be inhabitable for long-term indoor use without the ceiling being significantly higher.

- Optimisation and reduction of steel structural members was considered throughout the design process. The steel rafters are spaced 80cm apart (instead of the typical 60cm), reducing material while adhering to the sizes of available 4 x 8 ft bison board sheets that the rafters must support. The roof is designed holistically with consideration of all parts e.g., the length of each rafter is in exact accordance with the number and size of terracotta tiles required.

- Least amount of demolition was considered. The client had initially suggested in reducing the height of the southeast walls to achieve a slope. However, this was found to be unnecessary as this would not achieve the required slope. The proposed final solution requires only slight demolition above the southeast entry door, while requiring the north and northwest walls to be slightly raised by 28cm.

- A ridge beam is the solution for the peak of the roof, where the two sloping rafters meet. This was selected as a way of structurally framing the roof and avoiding any horizontal tie members, which the client wanted minimised as it made the roof appear too busy.

- Other design considerations: Additional overhang of 3 feet has been provided for the south-most wall and east-most wall, giving greater protection to the walls and especially for the east garden-facing kitchen window. Wood columns are positioned in harmony with verandah and roof. Gutter is proposed at the entrance.

Miscellaneous Notes

- The bison board should have been undercoated before being lifted into place, as this would have saved significant time (in having to paint the surface from underneath).

- The concrete columns are absolutely useless in this small one-storey building. The walls should have been built solely in double brick which would have saved a tremendous amount of the original budget.

- On a positive note, after the completion of the roof there was almost no leftover construction waste. The amount that was there I could have carried away with my own hands on the back of a two-wheeler.

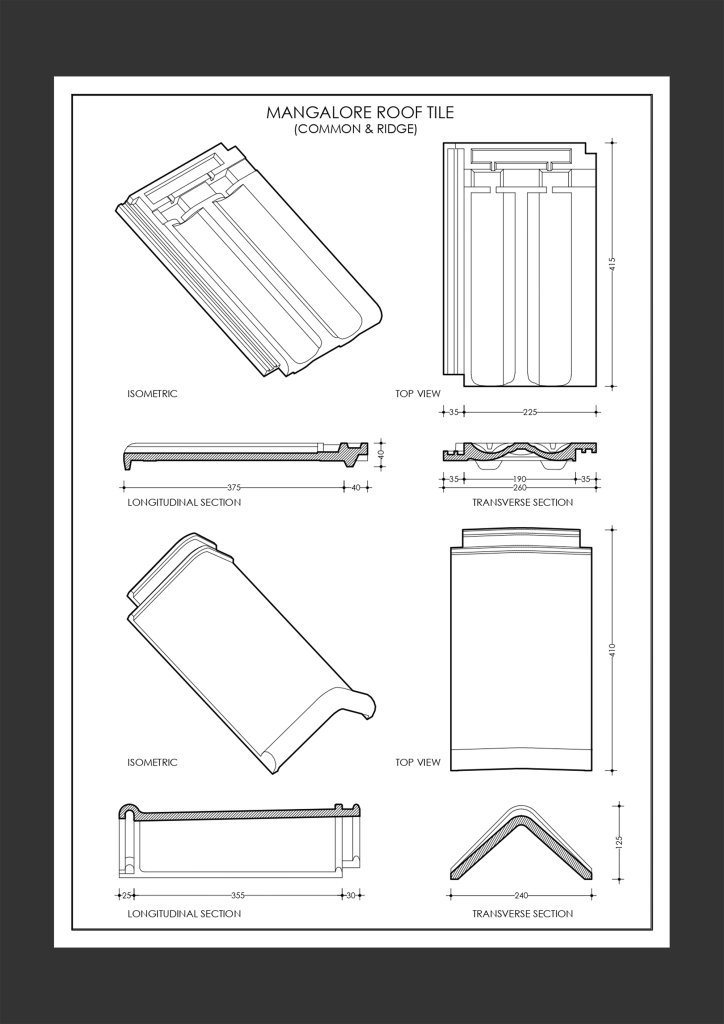

- Some interchangeable terms regarding the roof construction are: battens and purlins; rafters and reapers; bison board and cement particle board. Nomenclature is dependent on the locale.

- Use Mangalore Tiles with double grooves for optimal waterproofing.

👍🏻👍🏻 great work..

Great read as always! Especially liking the “how not to” parts and how you resolved them.

Hey. Thanks. Nice read and actually helpful. Still wandering if you can also put something else than the GI sheet especially in a tropical climate?

Something less costly so to say