When assigned with designing a home – whether for singular or multiple people – I find that it is my lived experience of spaces that prove to be intrinsically valuable. The moments that rebound and cling to me as I travel the palace that is memory. These experiences, reanimated in my minds eye, are often much more powerful in imagination and meaning than the reproduced images I have seen of architecture I admire.

‘…we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.’

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

I am currently tasked with designing in collaboration with others, a peculiar residential project in the Gujarati city of Ahmedabad, northwestern India. It is a city I have been to, almost four years ago from today. Fond memories stir within me when I think of that city of blistering dry heat, sitting on a crossroad of history. I have tasted its sweet street food, crossed its bustling roads, and explored some of its legendary institutions. Ahmedabad is where Gandhi built humbly his ashram.1 Where Corbusier designed freely for the Sarabhais. Where Kahn designed intuitively an entire university campus. Where Doshi helped foster generations of Indian minds.

Back then, I was in Ahmedabad with a small group of colleagues, Indian and foreign. We lodged in the old French Haveli within the heart of Ahmedabad’s Old City.2 The narrow streets pulsed with life of all generations. Kids in bright uniforms with neatly cut or braided hair walking home from school. The elderly chatting on the otlas.3 Pigeons and parrots perched on whatever built form allowed. Cows strode the streets boldly without equal, bearing horns curved and longer than any human limb. Squirrels paced relentlessly up and down the walls of homes built side by side – a neighbourhood in perpetual embrace.

The French Haveli was built with a chowk (courtyard) at its core. The rooms revolved around it, encompassing the penetrating daylight. Within this upward peering space hung a large hinchko (wooden swing), supported by intricate cast iron chains. I stayed in a room on the second floor (or was it the first?) that had its own balcony, which I think also functioned as the double-height portico for the main entrance. It was a room I surely made the most of. The balcony protruded towards the public realm so much so that it was so close to the next-door neighbour, that I could easily watch their TV, or even jump across into the living room if I willed.

The haveli with its intimate rooms and tight corridors bore the scent of the old hard wood that made part of its structure, material likely procured from other parts of the subcontinent, perhaps as far as Burma. Warm light filtered through the small glass windows and jaalis of wood, or pierced through the fine gaps between the shutters and their frames.4 In the dark hours of the heat-filled night, the French Haveli was cloaked in subdued yellows trimmed in teak.

What made it French I cannot remember. I don’t recall any wine (Gujarat is a dry state). Was it Indian with French characteristics? An unknown. Perhaps its original owners were French merchants or missionaries. Or perhaps during some interval of time, it was the French occupants that left such a lasting impression upon the place that it now bears the nationality as a result.

My last memory of the French Haveli was the breakfast we had to leave behind, as no one told the cook that we were leaving early to print our projects. We essentially walked out on a banquet of fruits, salad, breads, and some of the best scrambled eggs I have ever had. In my displeasure, I pocketed a couple pieces of toast and a scoop of scrambled eggs to take away with me and eat while on the rickshaw we left upon. So not all that food was made in vain.

The French Haveli is the first thing my mind harked back to when pondering the design of a residential building belonging to the same city. A deep concern of mine, intensified by the thousands of kilometres distance between myself and the site, is the conception of a building specific to its context. Architecturally, the last thing that is needed is a building that feels that it could be anywhere. We have enough of those kinds of buildings in the world. Hence, I am compelled to read the city’s history. Naturally my own history is most accessible and, after that, the studio’s library has more books on A’bad than any other city.

The courtyard of the Haveli is what I perceive capable of being translated into this new project. In size no more than a few metres in breadth. It is a volume of light penetrating the centre of the plan, shared by each different floor. The immensity of this vertical space is to solder a connection between the multiple floors, through diffuse light, obscured visuals, the flow of air, and muffled sounds. Other devices may end up becoming integrating with it, such as the staircase or front entrance. Time and the clients will tell. Standing on the ground floor (or even basement) one can look up and feel the presence of something above and beyond. The verticality is accentuated from the inside, not just the outside, as so often is the case with multi-storey buildings. Things are to feel more within reach, just like most homes should.

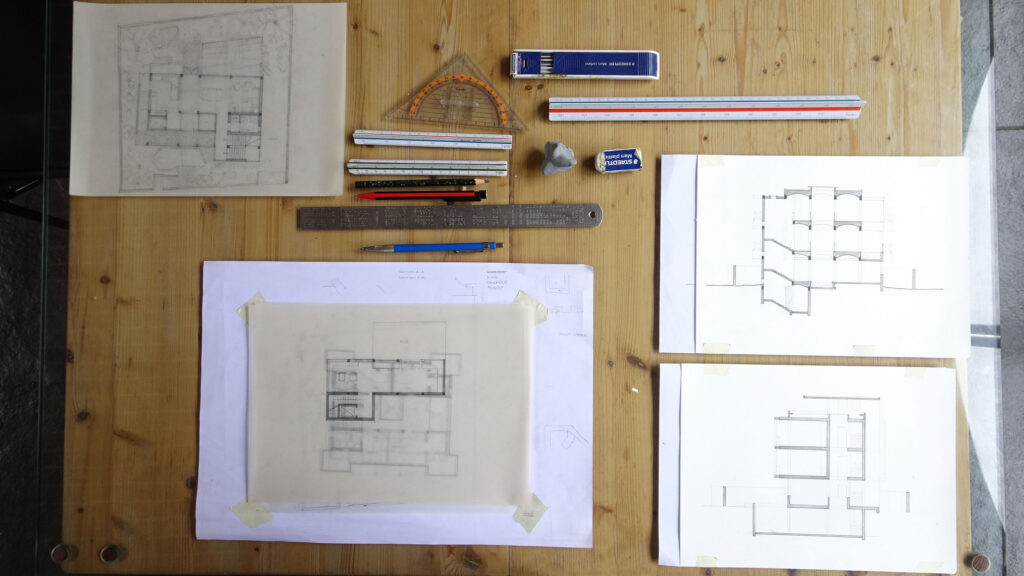

Such ideas as this floating around my head end up in pencil and paper. For to draw is to think. In fact, almost everything I’ve been doing regarding this project has been hand drawn. Anti-computer. I’ve even got the interns working alongside me to daydream in graphite. Even though the design will eventually be translated digitally, it doesn’t matter at this early stage. There’s nothing to lose. Each pencil line is a thought, not a command, as it would be predominantly on a computer program.

I also find it to be quite the meditative experience when drafting by hand, even with meeting deadlines fast approaching. Which helps because currently I am juggling between two significant projects. One that is a fifteen minute drive from my doorstep, another located on the other side of the country. One being constructed as we speak, another having its design being moulded like clay, day by day. Demanding responsibilities, but not unwanted during the strange times we live in.

I won’t describe the brief of the A’bad project for now. For it will take a bit of time and thought to articulate it well. There is not a particular word I can think of that would pin down the intricacies of the building’s program. The closest is perhaps the word shelter, but this is far too reductive. That’s what I find intriguing about the nature of this project – it can’t be easily described.

When I first heard about this Ahmedabad project, and of the reputation of those we’re collaborating with, I thought it would be cool for myself to be able to influence a brick or two in this faraway, ancient city. And I will stick to that. Since we’ve had three meetings so far regarding the conceptual phase, perhaps by now I already have. To me that’s an interesting thought.

1. The word Ashram bears many connotations alongside it’s meanings, of spiritual hermitage or spiritual retreat. Through my own experience I would be more inclined to define an Ashram as a community with unifying aspirations.

2. Haveli translates to palace or mansion. It is derived from the Arabic word hawali, meaning “partition” or “private space”.

3. Otla is a Gujurati name for a type of entrance common throughout the region, that is stepped and with enough room for sitting in comfort to enjoy the public street life.

4. Jaali is the Indian name for perforated or latticed screens and walls, made in a variety of materials such as stone, wood and brick. A common defining aspect is that they are constructed with ornamental geometrical patterns.