I aim to reveal my thoughts in the design process of a handrail conceived and fabricated over a year ago. The intention is to give insight to curious others of a way of designing for the most minute of details. The method bears resemblance to the holistic approach needed in the design of buildings as a whole. Where, to create a solution, one needs to respond to the variety of interdependent parts that make the problem, as is often the case when constructing four walls, a roof, and the rest that inevitably follows. For a handrail, the scope is of course much smaller, but the attitude is no less different. The process I am about to describe can be seen as rigorous, meticulous and refined, or perhaps… arbitrary, cumbersome and extreme. Nevertheless, I claim that the desired outcome was undoubtedly achieved.

That being; simplicity.

The handrail is one amongst many architectural details I have designed over the past years. I have selected it for this discourse as it best encapsulates my sense of design. I am sure that for some — perhaps many of you — this way of problem solving will resonate with you. For those unfamiliar with people working in the field of architecture, building and construction — please bear with me — for I am about to tell the story of a handrail.

Details, when they are successful, are not mere decoration.

— Peter Zumthor

They do not distract or entertain. They lead to an understanding of the whole of which they are an inherent part.

April-May 2020, the first lockdown of India was in full-swing. Construction of the project I was responsible for (a retreat/boutique hotel) grinded to a halt, without any idea of when it may recommence. Less focus was needed on the large-scale building activities. Small-scale works; a new reception, a new driver’s unit, and slight renovations to the existing buildings, were now given full attention. There came a timely opportunity to respond to the client’s request for a handrail to be designed and installed for the existing building’s staircase. It was a mystery to me as to why it lacked a handrail in the beginning. In the client’s request, the only parameter prescribed was that the handrail be made of wood. In India, this inherently means that it will be expensive.

I have always treated wood as an invaluable material. Coming to India, this attitude was drastically amplified due to its severe scarcity. It is economically impractical to construct with wood here. Instead, its utilisation in architecture — for those who can afford it — is limited to window frames, doors, cabinetry, furniture and the odd set of columns. The precious woods i.e. teak, rosewood, mahogany etc… are a rare resource and becoming more so year by year. It is always a remarkable wonder to see such wood abundant in older traditional buildings.

I was told early on that Kalimardu — a wood indigenous to the east coast of Tamil Nadu — would be the pragmatic choice for the handrail. Primarily because it is a third in cost compared to teak and readily available. Kalimardu is an incredibly strong and heavy wood, rich in beautiful dark colour. Its drawbacks being: difficult to work with (as are most hardwoods), and prone to warping at long lengths. Despite this, its cost-effectiveness alone was enough to be the deciding factor.

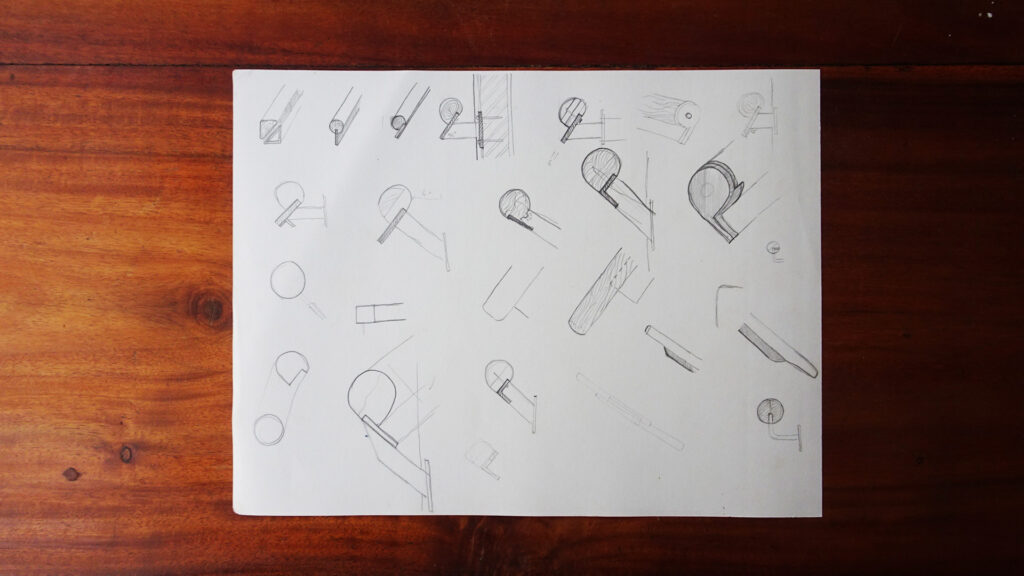

Contemplating the costly nature of wood in India, my first draft of the handrail design bore of frugal proportions. A slender length of wood circular in section, 45mm in diameter, questionably attached to the wall with mild steel brackets. I was uncertain about how exactly the handrail would be mounted to the existing masonry wall. To gain a valid understanding, I was advised to consult Mohan, the contractor.

Within a day or two, I had visited the construction site around noon to find Mohan, where the concrete roof of the reception building had been recently cast. We spoke under the shade of the wooden scaffolding and the canopy of a nearby cashew tree.

I asked Mohan how he would ordinarily mount a handrail to the side of a wall. In typical Mohan fashion, he first explained the technique by gesturing with his hands and fingers. ‘Tuk, tuk, tuk…’, he would utter while indicating a screw, bolt or nail being fixed into place. Either misunderstanding or wishing no millimetre of doubt, I got him to sketch the idea in my notepad. If paper were unavailable at times like this he would draw on the red earth with his fingers or a stick. Recalling some of the chicken scratches produced by my teachers at university, Mohan would put a fair amount of them to shame.

The answer to my question was simple really:

A small cavity is to be dug out from the masonry at the point of the bracket’s insertion. Struts are to be welded to the end of the bracket for support against movement, then inserted into the cavity, which is soon filled by plain cement concrete, firmly fixing it into place.

Mohan mentioned that the greater the use of the handrail, say, for a public building like a hospital, then the greater number of struts are required to handle the forces of multiple people.

Upon returning to the studio I decided to start afresh with the handrail design, as I was unhappy with its overall aesthetic. Not solely for its run-of-the-mill design, but because within its surroundings — an interior of exposed concrete structure, white plastered walls and jet black Cuddapah flooring — it would have appeared as a meek noodle as opposed to a length of sturdy solid wood one could depend on. For that reason, I put aside the handrail design for a week or so, to ponder upon in the back of my mind.

I feel it is worth mentioning that most of the ideas that occur to me — most of the ones that matter — occur to me not while sitting at a desk, but while walking or cycling from place to place. Whether that be from home to work in the morning or from work to a cafe at noon; or better yet, walking purely for the sake of walking. A phenomena suggesting that movement in the body stirs movement in the mind. The lapse of pressure, the momentary freedom from multiple tasks, allows the mind to become highly receptive. An idea might fall before me like a leaf from a tree. Or it might slap me in the face, like so often does a seed or a beetle as I am riding.

I imagine the handrail to be more than just a plank of wood stuck to a wall. It is a welcoming guide. A strong companion. A limb to lean on. An amiable gesture. If ‘the door handle is the handshake of the building’, as Juhani Pallasmaa so eloquently phrased,1 then: the handrail is the building’s arm outstretched to maintain another’s balance.

I recall the sources I looked at for inspiration via books and online material. Carlo Scarpa, Peter Zumthor and Louis Kahn would have been the first architects to come to mind. Scarpa’s work, gratifying in its intricacy and zealousness. Zumthor’s, in its austerity and placidity. Kahn’s, in its robustness and grace. None of which I would describe as sculptural or plastic; all of which I would describe as beautiful, timeless and true to material and craft. The woodwork of George Nakashima, although focused on furniture, I often refer to for any wooden details. Another, lesser known, influential work was a handrail made by Adam Markowitz, an Australian architect and furniture maker, installed in a residence called Cabbage House, designed by Peter Stutchbury. I had glimpsed the making of this particular handrail unfold on Markowitz’s Instagram account.

All these various references floated about my head before I realised another — more immediate and local — seminal work to reference.

‘There is nothing new under the sun’

Solomon

Photo credits: Henrik Dutz. 28 • 01 • 2019

The handrails inside Golconde’s stairwell had sprung from my memory.2 Framing the sides of each run of its stairs are thick lengths of splendid teak, mounted laterally to gleaming lime plastered walls and concrete parapets with handcrafted brass pipes. Each individual teak board equivalent in size to a diving board. The wall-mounted fixtures are a difficult detail to fabricate; the brass members having been custom-made in the Ashram’s metal workshop some eighty years ago.

Generally, one would seek fixtures that are easily available on the market. In most instances this would be the most logical approach. However, both the beauty and drag of working in Auroville is that the local market is considerably limited. The major cities i.e. Chennai, Bangalore, Hyderabad etc… is where mass produced and standardised parts are easy to acquire. Here, however, importing is often more expensive than custom making the item in a local workshop. Hence, fabricating a brass pipe detail similar to the one at Golconde was a daring, yet genuine, possibility.

For the wall-mounting fixture I selected brass over other metals for several reasons. The other contenders being mild steel and stainless steel. Mild steel would be by far the cheapest and strongest, but requires to be painted and repainted over the long-term to avoid rust, particularly in a subtropical climate. Brass and stainless steel cost approximately the same, although brass has better resale value. I personally refrain from the use of stainless steel wherever possible. It is a cold, voiceless material. Touching its cold metallic surface can cause quick sharp pain, especially for older hands. Coupling this with hard-edged ‘modern’ design, it can be a relatively painful material to grasp.3 My tendency is to use it only when absolutely necessary, like for the handrail of a swimming pool where anti-corrosion and low maintenance is essential . Another lesser known factor is that stainless steel is less detectable by the visually impaired due to its poor acoustic qualities.4

As I wanted the wall-mounting fixture to complement the rich colour and texture of the wooden handrail — brass was the ideal choice from the beginning. Brass carries a darker patina over time if left unpolished. I find this a quality to be desired, where the material carries the passage of time. Aesthetically, wood and brass harmonise with each other like an Indian bride and her golden jewels.

The disadvantage of using brass in this circumstance was less dependent on its material qualities, and more so on the complexity of the final design. Whether the sectional sizes and craftsmanship needed to make it were available. The handrails of Golconde gave me the impetus to keep pursuing the idea.

The final handrail design is extravagant in material and simple in geometry. Extravagant in the sense that the wood is heavily sized in section, so as to give it a formidable presence amidst the large concrete columns and beams. Evoking the same robustness of its surroundings. However, its weight is contradicted by the delicate manner in which it is lifted afloat in space, by the series of nimble brass pipes projecting from the adjoining white wall. The only embellishment are the exposed brass caps revealed across the Kalimardu surface at regular intervals, neatly capping the ends of each pipe.

By previously referencing the work of Scarpa, I had initially been tempted to produce something exuberantly sophisticated. Since the budget was open-ended I had no cost limitations per say. Yet, rather than push solely for novelty and form,5 I instead would let the qualities and limitations of material and craft principally dictate the design. There is such a potential outcome as over-done, overcooked or over-designed, which unnecessarily involves more time and money. This a designer should be wary to steer away from. It is better to practice restraint than be carelessly exorbitant.

When in doubt, reduce; when not in doubt, surely reduce

Gurjeet Matharoo

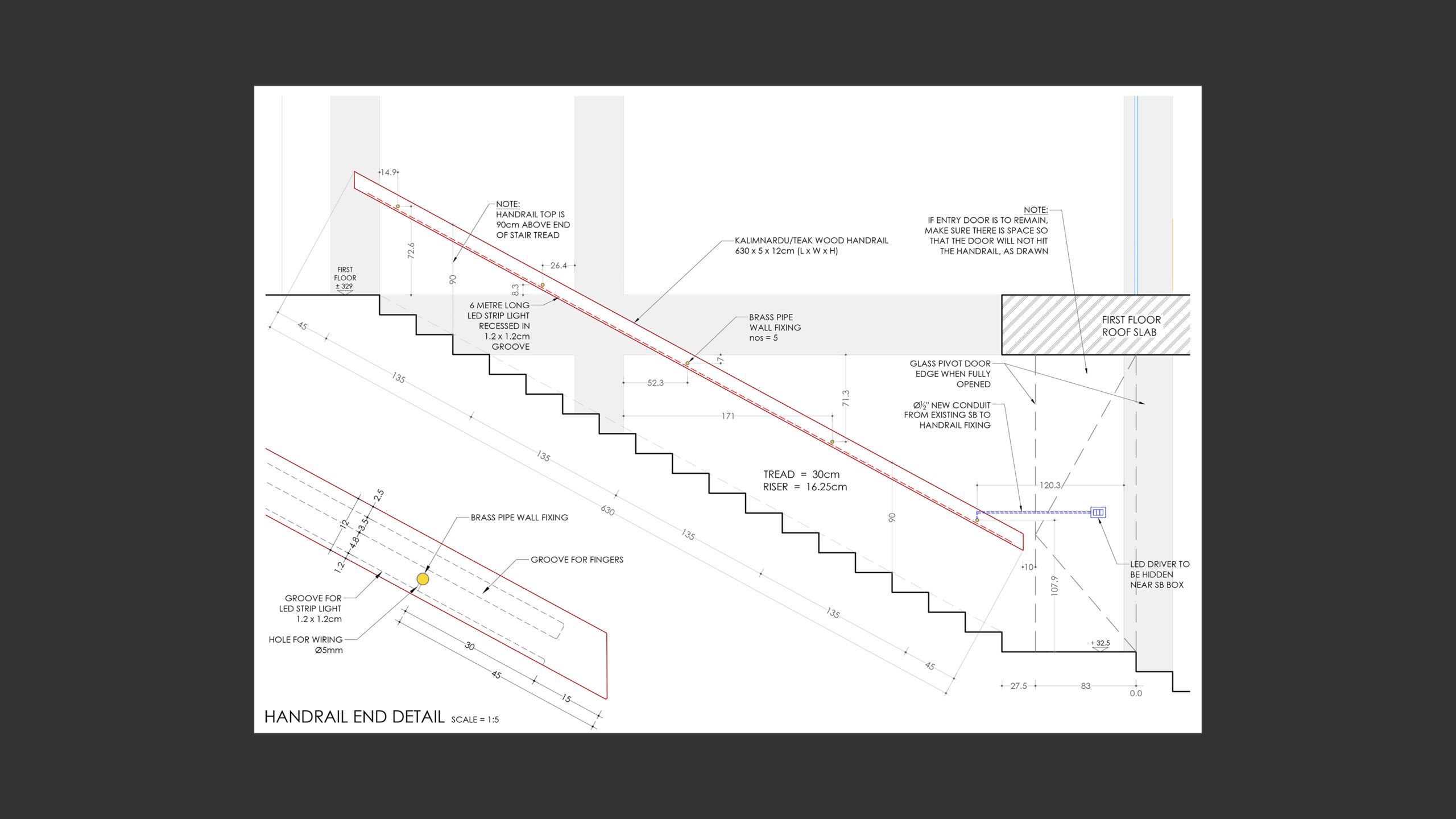

The handrail’s technical details are described as follows:*

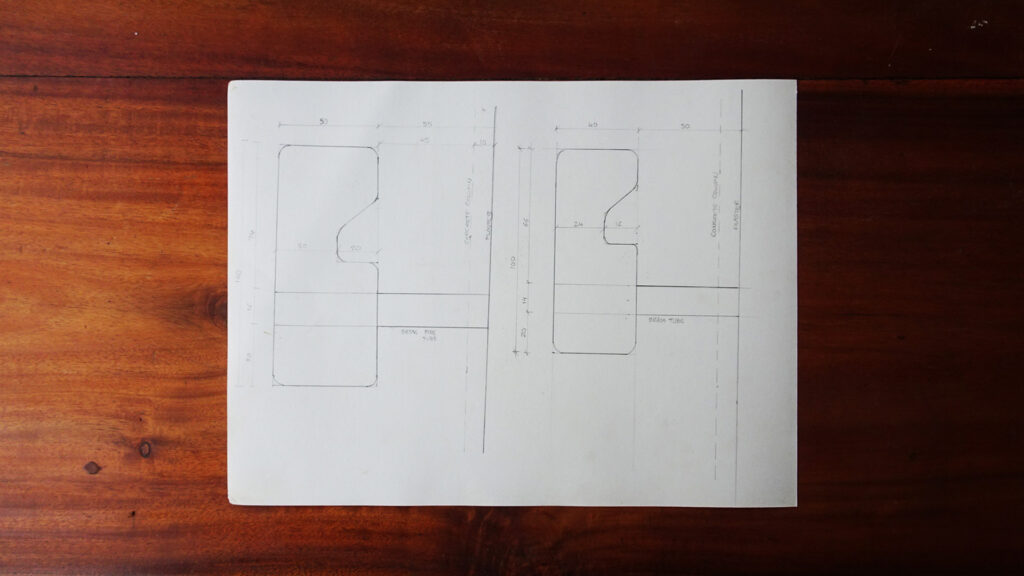

A 6 metre long handrail of local Kalimardu wood. As Kalimardu is rarely unavailable in such length, the total consists of two pieces combined with a mortise and tenon joint. The handrail is rectangular in section; 5cm wide and 12cm deep, with 5mm rounding at the corners. Spaced 4.5cm away from the wall surface. Running across the less-seen, wall-facing surface of the wooden section is a triangular groove, allowing for better hand grip and dexterity for the user to balance their weight. This groove stops short of both ends of the handrails to maintain a bare geometry, thereby concealing the ergonomic touch and making it unexpected.

The wooden section is connected laterally to the wall with five brass pipes, 2cm in diameter, each of which screws onto a compatible mild steel pipe fixed and buried inside the masonry wall with plain cement concrete. The wooden section is locked in place between a welded brass ring and a brass screw cap. This brass screw cap is purposefully exposed and flush with the surface of the wood. The cap is slotted to allow for easy installation or removal with a flathead screwdriver. The wooden section has an underside groove as a provision for an LED strip light. This parameter is why the mounting fixtures are hollow pipes instead of solid rods, as it allows wiring to pass through hidden.

*Inclusive of Mohan’s modification, described in the following paragraphs.

I showed a drawing of the latest handrail design to Mohan while referencing Golconde in conversation. “You draw it, I make it, no problem…”, was Mohan’s response to my idea, which he says whenever I express concern for the feasibility of a sophisticated task. Later, I was to find out that he himself had done some small work on Golconde, installing a handrail for a few steps near the entrance (to me that is equivalent of him having worked on the Louvre).

Over the course of a few weeks Mohan and his carpentry team executed the handrail design with a slight yet integral modification, unnoticeable on the surface. He had cleverly improvised how the brass pipe would connect to the mild steel pipe hidden in the wall. I had originally specified that the brass pipe would be tack-welded to the MS pipe, as I believed this to be the most feasible method available (I, being a novice in metalwork). Instead, he went to a metal workshop in Pondy and had the ends of both pipes machined so that the brass pipe would screw onto the MS pipe. No welding involved. A clean detail. In my eyes Mohan outdid himself and appeared jubilant with having accomplished the challenging task. Looking back, I had underestimated the capability of the local craftsmanship at my disposal. Luckily, I was — and still am — surrounded by people with the know-how, patience and determination to innovate.

When I saw the handrail installed for the first time, I noticed in one location some tiny marks blemishing the surface of the Kalimardu wood. With a puzzled look I asked Mohan what caused them.

He said rats…

…rats!

‘Rats don’t eat wood, do they?’ I asked in bewilderment. ‘No, they don’t…’ he replied. He explained that in his experience this had never occurred. Nor had he heard of it from anyone else. It turns out, that rats definitely do not eat wood. But, sometimes, they do enjoy a tasty varnish. The rat had chewed on the handrail during the night after varnishing.6 I was actually more amused than bothered by it. Furthermore, I was still impressed by the overall result having been translated from pencil and paper to wood and brass.

I do not blame the rat. Looking at the final result, I suppose it does look delicious.

Fundamental to the realisation of the design was that it was informed by material and craft. The design made only valid progress once precedent was researched, material carefully understood, and a true liaison between designer and maker established. Pencil and paper provided the means to conceptualise and communicate the ideas early on in the most intuitive and efficient manner. After the mediocre first draft, all notions of a preconceived idea were slashed, allowing the creative process to flow and ferment over time. Inspiration and daring was gained by studying various examples of exceptional designers. Discussions with Mohan enabled an understanding of the essential parameters and limitations that could be negotiated through design. Intrinsically, Mohan embraced the challenge put forth.

It is argued that simplicity was achieved through practising restraint and seeking a balance between the variables. A circumstance where not a thing needs to be added or subtracted.

Not all architectural details demand an extensive process or criticality. As the designer’s repertoire of material and craft develops, so too does the ease in conceptualising architectural details. For the handrail, it was a dialogue between two precious materials — wood and brass — that compelled its rigorous and methodical creative process. A pursuit of perfection — a pursuit of the pucca pucca — is what drove the meticulousness and tenacity of the designer.

1. Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 1996), 62.

2. Golconde, a dormitory building of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry, has always been a source of inspiration for me since I laid eyes upon it in August 2016. Designed by Czech-American architects Antonin Raymond and Francis Sammer, and Japanese-American architect and famed furniture maker George Nakashima, Golconde is an exemplar of Modern Architecture, strenuously built by the unskilled hands of the ashramites themselves, during the resource scarce period of World War II.

3. My negative bias towards stainless steel is amplified by my memories of the door handles within the Melbourne School of Design. To enter one of the many tutorial rooms, one had to firmly grab a cold sharp-edged square handle of stainless steel, and pull with full force as the door was terribly heavy; its hydraulics always in disrepair. Often this was painfully accomplished with one hand, as the other was — holding on to dear life — a hefty architectural model and a folio of A1 drawings.

4. The disadvantages of stainless steel I learnt in discussion with my thesis supervisor, Greg Missingham, during my last months at the University of Melbourne.

5. Novelty and appearance must not be the only factors deserving of attention. With these two one can easily get carried away and miss out on the other vital parameters responding to human needs, like ergonomics, material availability, costs, maintenance, safety, durability and ease or difficulty of fabrication. It is integral that all these parameters be thought of and considered simultaneously, to come to a solution where the advantages outweigh the disadvantages.

6. To avoid this happening again, the handrail should have be stored in an enclosed room, rather than have been left undercover outside.