Sitting ahead is the Arabian Sea. I sit on the Malabar Coast. Like any sea view it is a glorious open expanse, particularly to my groggy eyes after having hopped off an overnight sleeper bus but an hour earlier. There is an idleness in the air, owed to the surrounding neighborhood yet to arise from slumber. Eight years is the length of time since I last gazed upon this sea’s shimmering depths. That was in Gokarna. Now I am in Kozhikode. Sitting ahead is an apt way to describe it, for as a sea and part of the greater Indian Ocean it does appear to just sit there peacefully, with tides of shallow breath, as if it has never known a storm.1 At least that is my impression, for it no doubt appears calmer than the Bay of Bengal, in similar manner to how I perceive the Indian Ocean to be calmer than the Great Pacific.2 It is both my first day here in this ancient port town—now city—and within the southern Indian state of Kerala. In my short itinerary Kozhikode is a stopover on the way to Kochin to attend the 2022-23 Kochi Biennale, the South Asian aspiring equivalent of the Venice Biennale.3 It is not a necessary stopover as the bus would have continued onward to Kochin, however, I had a place in mind to visit, a place that had long piqued my curiosity… a terracotta tile factory.

Evidently, I had come to the right place to find such a factory, as Kozhikode’s cityscape was capped with countless terracotta pitched roofs, more so than I had ever seen before.4 Most Indian cities in the tropics have foregone the pitched roof in favour of the flat concrete terrace much to their detriment climatically, but fortunately not here. Thus, the city has an earthly charm about it in keeping with the image of Kerala as a whole; a land that has strongly held onto its cultural roots, exemplified in its architectural vernacular. Before exploring the terracotta tile factory, I will first explain my knowledge and profound interest in terracotta tiles, specifically the Mangalore Tile, the prolific roofing material of South India.

Etymology & History

Semantically, the name Mangalore Tile is a bit of a misnomer, as not all Mangalore Tiles come from Mangalore, a city located in the southern tip of Karnataka; skirting the northern border of Kerala (a few hours drive north of Kozhikode). For the most part of my experience in India, I have observed that this terracotta roof tile is colloquially known as Mangalore Tile, no matter the fact of where it was precisely manufactured, which is found out by checking the ‘made in: location’ embellished on the bottom of the tile. This is its common-most name as I have come across it, subject to my time well spent in Tamil Nadu, where to call it anything else can invite confusion. Maybe in Kerala it goes by another name, in Karnataka another, and, perhaps specifically in Mangalore they are just called roof tiles. Be that as it may, and, to complicate the subject further, the design of the Mangalore Tile itself does not originate from Mangalore or even India, but from France, where it is commonly known there and in other parts of the world, including Australia, as the Marseille Tile.5

This type of interlocking tile was invented in 1851 by the Gilardoni brothers in Alsace in north-eastern France. Soon it was adopted, then adapted, by other tileries6 across the country, most significantly within Marseille. From here it was exported across the world.7 It was thanks to the work of German missionary-engineer George Plebst (1823–1888) that the tile based on the Marseille pattern, that would become later known as the Mangalore Tile, was introduced to India.8 Therefore, in a similar twist of tongue, the Marseille tile as an idea did not originate in Marseille, just like how the Mangalore Tile as a product does not necessarily originate in Mangalore.

Architectural Significance

After three-and-a-half years of professional experience in the field of architecture in Auroville, I have spent a great many hours designing and drafting buildings roofed with the humble Mangalore Tile, in varying manners of shapes and sizes be it gable, pyramid, dutch-hipped and so on, where the main problem usually lies in reconciling the roof pattern and pitch with the wall layout. Besides my direct relationship with this material, I have also observed it cleverly used throughout Auroville by many brilliant architects or self-builders. This roof type often appears to be simpler than they actually are to build, comparatively to a typical concrete terrace, and particularly if the roof is to be insulated (and in a tropical climate under the rays of the harsh sun you would want it to be). Done well and done mindfully, whether designed by architect or laymen, they do make for roofs of beauty, timelessness and elegance in simplicity. Furthermore, beyond this material’s notable aesthetic qualities, it is its social and cultural merits that I believe truly give it its architectural significance. For the Mangalore Tile is the most enduringly conspicuous roofing material in South India. No other roofing material—tile, sheet, channel, or panel—is both as recognisable and appreciated to the trained and untrained eye. It is used in city or village, on the coast or inland, up in the hills or upon the flats. Diverse not only in the location of its use, but also—and more so—by the different building types it covers and the variety of occupants it shelters. It can be found roofing sheds, porticoes, gateways, toilets, factories, offices, workshops, bazaars, fish markets, restaurants, cafes, schools, churches, mosques, temples, residences, hotels, resorts, mansions and palaces. Demonstrably, this means that this humble reddish clay tile subverts socio-economic disparities, being readily accessible to all in some form of shelter or another, without any connotations towards any class, caste, or creed.

The Commonwealth Tile Factory

Now that we have an understanding of the Mangalore Tile’s value, as indicated at the beginning, this discourse will converge to a place of its very manufacturing: The Commonwealth Tile Factory. Located in the leafy village of Feroke, about twenty minutes south of Kozhikode’s city-centre via auto-rickshaw, the Commonwealth Tile Factory’s street appearance is straight out of a Victorian-era picture book, the kind of scene one can imagine as a lithograph. All the walls are of load-bearing brick including the chimney piercing the sky. It is a fortress of fired clay, roofed with the very product it manufactures. Architecturally, it is certainly heritage, but I would not label it antiquated, a relic only of the Industrial Revolution, as here it still stands more than a hundred-and-twenty years old fulfilling its mission to meet the demands of today.

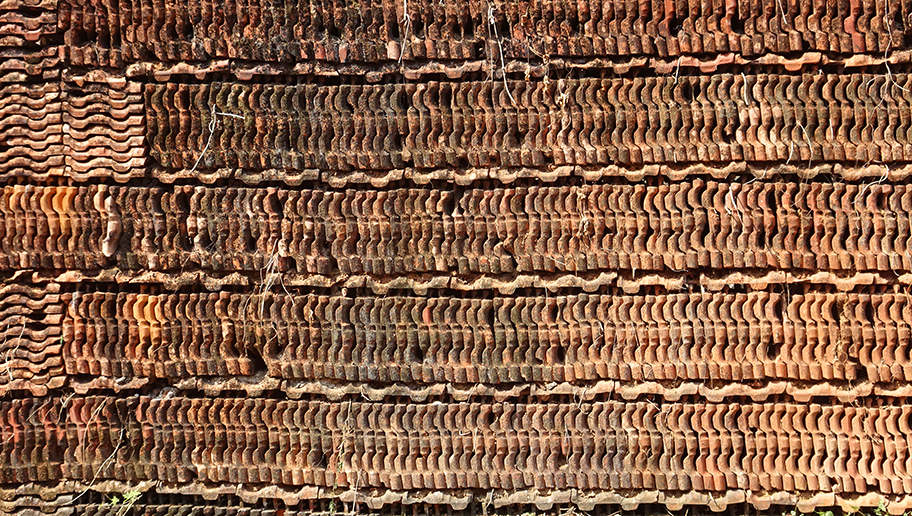

Displayed before the factory proper is a massive field, barren of vegetation, but occupied by mountains of countless stacked Mangalore Tiles, awaiting their turn to be loaded into the backs of lorries and transported across the country. A friendly worker we approached led us to the management office to gain permission to tour the factory. After a little waiting and the signing of a short acutely worded document, stating that they held absolutely no responsibility for any possible harm or injury, we began to explore the factory guided by a member of the staff. I would have learnt his name if it were not for the thrum of machinery permeating the air, that still hampered me when asking him a second and third time. I will narrate through snippets—with emphasis on the idiosyncrasies and atmosphere—what I primarily recollect from this experience, rather than detail the entire manufacturing process for that is beyond my scope.

The first area we were shown was a large pit where two varieties of clay were dumped from the back of a lorry, to then be shoveled and extracted into a submerged room-sized mixing machine. A small team of four or five men dressed in soiled coloured shirts and lungis toiled away at this task under the shade of a corrugated metal roof. This was the only area where the smell of earth outweighed that of soot and oiled machinery.

Next, entering the mammoth of a building that is the factory, is a series of enclosed spaces where steel belts hurriedly carried from machine to machine the mixed clay, to then be compacted and segmented into neat individual volumes. These rooms were dark. Not the ‘I see nothing’ kind, but the ‘place in the shade’ kind, completely protected from the sun. More than dark they were loud, and visibly just as dangerous. Most of the human pathways ran directly beside and underneath these fast moving conveyor belts and lines, where in places they were easily lower than six feet in height, meaning a tall person working here would always be at risk of either getting coat-hangered or receiving an unwanted haircut.

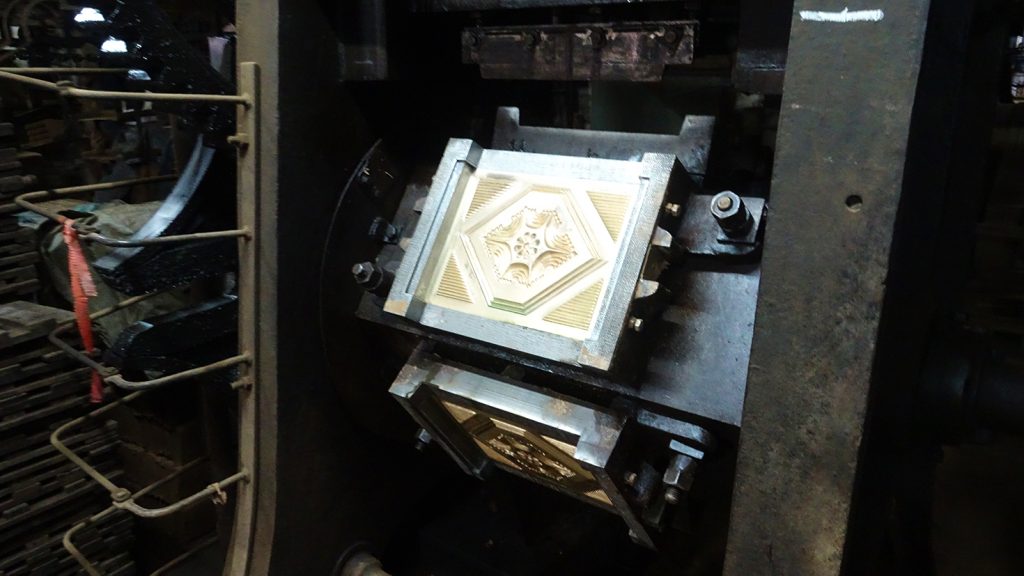

Then moving on, comes a large double-height space where the majority of workers were located and the machinery slows down from rushing river to steady stream as things begin to require a human touch. The air is still awash with noise but is more tolerable, and the smells are varying of: part engine, part shed, part clay and part sweat. By this point the clay has been shaped into rectangular loafs with a tube-like texture on its longer sides, the colour more grey than red. After passing quality control, the clay is then slam-pressed into a mould by a massive heavy machine—probably the most expensive piece of equipment in the factory—with the mould-plate made of either solid bronze or brass. Of the workers, some were handling the machinery, some were checking for imperfections, and others were carrying the loads of the recently pressed tiles away. All were glinting with sweat.

The tiles were being carried in back-breaking batches up a precarious looking timbre staircase that was far too narrow considering the human traffic and nature of its task. Reaching the top of the staircase after some trepidation is where my sense of direction diminished as the internal atmosphere became darkened and contained, feeling less like an industrial factory and more like the cargo holds of an old East Indianman.9 Through the dark we were led to an expansive room of wooden decking with numerous hatches pocketing its surface in regular intervals. Stacks of casuarina were lined against the walls and soot covered anything of lighter shade. Soon, we realised this deck below our feet was directly above the kilns, where the firewood would be spent from above by dropping it vertically through the hatches. We were demonstrated this process by an active kiln. A shot of hot air flew upwards as soon as the was hatch opened. Looking down was the closest thing to magma I have ever seen. A worker close by dropped a length of casuarina into the fiery gullet, increasing its heat to a temperature where I felt immediate gratitude once the hatch was shut closed.

Moving onward—where I cannot recall whether there was another flight of stairs—led us to the vast space-consuming repository that stored thousands of Mangalore Tiles. Racks upon racks of Mangalore Tiles are seen through aisles so long in length their ends seemed to disappear into vanishing point. It is a library with a collection of one title. Laid in the middle of these aisles are steel tracks where purpose-made railcars transport the tiles to-and-fro each end, making this a building with its own rail network. Here in this storehouse, these freshly moulded tiles are put to dry for weeks and when hardened they will be ready for freight and construction.

The final space revealed to us was one of the many kilns back below on the ground floor. Inside, bricks, blocks and tiles were partially stacked and arranged against the end walls and floor; the kiln yet to be filled. Size-wise, it was of an elongated bedroom and, typical of most wood-fueled brick kilns, its ceiling was vaulted and the entryway arched. The entryway I would argue was the most peculiar aspect of the kiln, for it had no door, not even a hint of an hinge. Instead—as I was told and soon observed—before firing, the entryway would be sealed by bricks, without mortar, then when the firing was completed it would be unsealed, again brick by brick. Thus, opening and closing the entryway moved at the pace of a bricklayer. How annoying would it be if someone were to leave their keys inside after sealing it up?

Finishing seeing the inside of the kiln completed the guided tour. We then made our way towards the light at the end of the tunnel that was the exit. Exposed again to sunlight, I looked around the open field of Mangalore Tiles. A metal tapping sound took my notice. Near the arched entry, a couple of workers are doing one last quality control test as they shift the tiles to form stacks. With a thin metal wire, a worker taps twice on a tile he has just picked up, checking its cohesive strength, then adds it to a pile and repeats. As we walk exiting the compound, I look back at the factory buildings, a prime example of beauty in the mundane, and appreciate it as the source of a material that I have grown fond of these many years.

1. Later, at an evening dinner at an eatery nearby Auroville, I would confirm this assumption about the Malabar Coast’s calm weather during a chance-encounter conversation with a medical student hailing from Kochin.

2. The strongest waves I have witnessed on the eastern shores of the Corromandel Coast make for average waves on most shores of east coast Australia. This can be judged by the sound of the waves just as easily as sight of them.

3. Kalicut is the anglicised name of Kozhikode and Kochi is the anglicised name of Kochin. In my experience these respective names are used equally inter-changeability, unlike Chennai which is rarely referred to as Madras (old), or Bangalore which is rarely referred to as Bengaluru (new). Though considering my short time in both these cities I could very much be wrong about this.

4. Auroville has its fair share of terracotta tiled roofs, as does the rest of Tamil Nadu, but I would say it is nothing in comparison to the Malabar Coast, where it is primarily manufactured.

5. For information of the Marseille Tile in relation to Australia, visit: https://acahuch.msd.unimelb.edu.au/miles-lewis-heritage-building-collection/marseille-roofing-tiles

6. Tilery definition: a kiln or field where tiles are made or burned

7. Robert Victor Johannes Varman, “The Marseilles Tile or French Pattern Tile in Australia,” Australian Society for Historical Archaeology Occasional Paper, No. 3 (2006): 1, https://asha.org.au/pdf/publications/OP03_Varman.pdf.

8. Ajay Kamalakaran, “How a German missionary changed the way houses were roofed in western India,” Scroll.in, January 24, 2023, https://scroll.in/magazine/1042123/how-a-german-missionary-changed-the-way-houses-were-roofed-in-western-india.

9. East Indianman: a class of large armed merchant ships that were used by the European powers between the 17th and 19th centuries to transport goods between Asia and Europe. Refer to link: https://beyond-the-shore.obsidianportal.com/wikis/ship-types.

What a beautifully written article! Love the descriptions, like the one where you talk about darkness not in terms of lumens but with casual everyday human phrases. The factory seems straight out of an animation movie, thanks for bringing this to us, would definitely want to visit it one day!

‘This was the only area where the smell of earth outweighed that of soot and oiled machinery.’

Love your ability to give a smell and feel of the place. So cool to think how something as mundane as a factory has been spitting out aesthetically significant material for decades – where all those tiles are now and how many roofs this factory has contributed to. Great read.