‘Pucca’, ‘pukka’, or ‘pacca’, is an Hindustani term1 that figuratively describes any dwelling constructed with a quality of permanence or long-lastingness. A good example is a terracotta tile roof being pucca – as they can last lifetimes – if well maintained. The opposite of pucca is kutcha, the quality of temporariness. A thatched roof made of palm leaf is hence – kutcha – as it will need to be reconstructed a multitude of times within a lifespan. Pucca will be the topic of this writing. However, it’s typical meaning is not at the core of my thoughts for this discussion.

I am interested in ‘pucca pucca’, a concept of which I encountered while in conversation with Mohan, a local building contractor with a tremendous amount of experience and wisdom in the Auroville/Tamil Nadu construction industry. Alongside his killer moustache, Mohan wears a subtle cheeky grin. I talk too fast for him; ‘tuk-tuk-tuk-tuk!’ was an impression he made of me recently. He’s a good teacher, with a pucca pucca method of explaining things simply. If we let him have his way, he could easily build our designs with basic sketches — but would do the details in a semi-ad hoc, semi-crafted way, likely to involve more concrete than necessary. Where architects may overkill it with the design, Mohan may overkill it with the actual construction.

In late December, 2019, Mohan and I met at the site. I believe this was our first meeting alone together. We were standing in the shade of a cashew tree, one of dozens scattered across the land. We are meeting to discuss and check over the markings for where the buildings are to be located. It is morning and there is a dry but tolerable heat. The previous day I had sent Mohan a site plan and, now on-site we were holding the A2 sheet, set in a plastic sleeve to protect it from the elements, although slightly wrinkled from being carried on a motorbike.

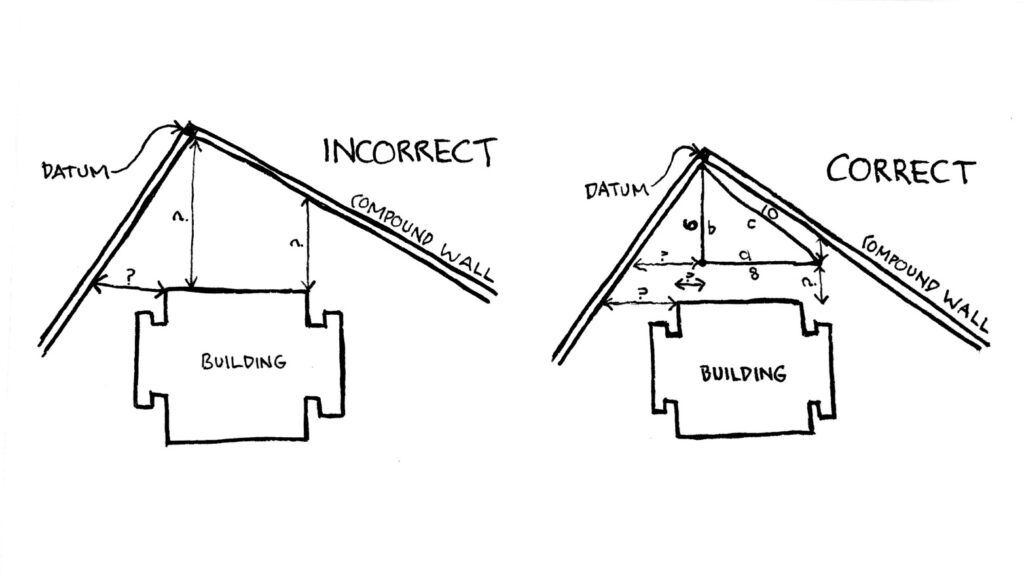

The builders mark the perimeters of the new buildings by sprinkling white powder chalk lines across the soil, or using string tautly tied to segments of steel reinforcement staked into the ground. Only one building had been marked so far. Instantly, I could tell by eye that it wasn’t in the correct position as we had planned. This was because I had not provided adequate dimensions in the drawing; I had made an error.

After some critical reflection, I know it was because I assumed – without truly knowing – how the buildings would be marked. The principal architect that oversees my work did not check. Usually I am of the habit to make sure my drawings are checked. But this time, it just did not occur.

I am determined to acknowledge and own my mistakes, so I stated that the drawing was wrong. Mohan responded by saying, ‘ah yes, you change on computer. You know, when Poppo would send me drawings – all drawn by hand – they would always be perfect, pucca’.

Poppo Pingel is a German Master Architect, teacher & archaeologist who has lived and worked in Auroville since its founding, some fifty years ago. He is responsible for training a great many men and women in design and/or construction, including Mohan.

‘it was pucca pucca…’

Mohan continues, ‘If there was a time when myself or my workers thought there was a mistake, we would ask Poppo and he would respond “check again, this time more carefully” and so we did and it was pucca pucca…’

And so I set off back to the studio, in pursuit of the pucca pucca. This delightful phrase I had not heard before, and only later that afternoon my colleague Saloni told me what it meant.

After learning the typical meaning and pondering it further, I knew that Mohan meant it in an atypical way. He meant that the drawing was ‘final,’ ‘for certain,’ a ‘finished piece.’ Obviously, its typical meaning of permanence doesn’t apply here. The quality of finality, is the core of what he meant, and the lesson I learnt that day.

Even though I knew that this drawn mistake was actually a rather light one in the grand scheme of things (I was there to check after all, and construction itself was a farcry from beginning); even though the cost of labour here is cheap and the task of marking out the lines requires no skilled labour;

A mistake is a mistake.

It would have no value at all if I didn’t learn from it, and that I believe I have done so. By writing this I am reminded further.

I fixed the drawing by that same evening, had it reviewed, and was on-site a couple of days later to check again (the site is a 15 minute drive from the studio). I found the markings to be all in good order. An old tall Neem tree that we had specified to be left untouched, was now a safe distance from any building perimeter, unlike what it would have been if my mistaken drawing was followed through with.

“Drawing is faster, & leaves less room for lies”

Le Corbusier

Drawings are the fruit of an architects labour. “I prefer drawings to talking. Drawing is faster, and leaves less room for lies,” as Le Corbusier once said.2 We designer’s have it luckier than orators, who must also be precise – but in their speech – as that is the primary tool of their trade, as drawings are ours. But the nature of the spoken word is by far and large at greater risk of being misunderstood.

The objective of the designer whose work is transitioning beyond speculation into fabrication, is to be precise in communication, through drawing and writing. Anything less than this, leaves room for doubt, mistakes, or ad hoc results.

Ad hoc is better than an outright mistake. I don’t depreciate the ad hoc (the majority of dwellings in India are self-built), but it leaves much greater risk for undesired results, especially if one aims to realise an idealistic vision in built form. This does not apply of course if the unexpected is desired, but that is another topic of discussion, another game that I personally would apply more to landscaping or small architectural details, rather than to entire structures.

Mohan happens to also be building a residence next door to my project’s site. It is good work, but has certain questionable aesthetic and material details. Nevertheless, it will certainly survive any cyclone the earth could potentially muster. While I was here, exploring the construction in progress, I witnessed the skills and craftsmanship of the builders, which has limitless potential if put to use by a skillful architect.

I am reaching a level as a professional, where my work can be labelled as pucca pucca, as it has been by some of my colleagues. That has been the pay off by maintaining a sense of determination and discipline, that I will keep wherever I go. That is the path, that is the aim.

1. The literal translation of pucca in Hindustani is ‘ripe, cooked, or experienced’, while kutcha means ‘unripe, raw, or inexperienced’.

2. That was just the first time I quoted Le Corbusier. I myself was never a diehard fan of the 20th century architect. This may have stemmed from me being three-quarters-asleep during my 8am lectures on architectural history in my bachelors. I respect his legacy, but am not captivated by him, perhaps too because I found Chandigarh to be somewhat disappointing as an Indian city.